In many ways, one week in Charleston is not enough. The city’s colorful buildings, shaded parks, and historical markers remind you that its importance to the American economy and culture dates back to Colonial times. Really getting to know Charleston would take months. There are the stately and bright private residences along The Battery, the old public market downtown with tourists shuffling between stalls, the College of Charleston and the Citadel, the USS Yorktown aircraft carrier parked in the marshes across the Cooper River at the end of the iconic Ravenel Bridge, and stoic Fort Sumter out near the harbor entrance in the distance. And yet a week as a visitor can be overwhelming. Everywhere you go you’re confronted with another attempt to reinforce – or redefine – what it is to be Southern. That confrontation is most immediate in Charleston’s famed food scene. From downhome to upscale everyone puts their own twist on classics like shrimp and grits and hushpuppies and everyone's trying to outdo everyone else, to be more southern, more real, more Charleston. It’s especially true of the bars and restaurants on one of Charleston’s hippest areas, upper King Street.

For instance, the bars “Proof” and “Prohibition” are both described as mildly Southern-themed places to get a drink. If you were to judge by their names and facades alone you may choose to visit one, not both, assuming them to be nearly identical. We went to both. At Proof, a dimly lit space with limited seating, bartenders mixed cocktails with names like Smoldering Manhattan, which, according to Garden & Gun magazine, “tastes intriguingly like an old library smells,” and served small bites like boiled peanut hummus. I opted instead for a glass of red wine, which tasted intriguingly like fruit, sugar, and alcohol, and a side of water, which may have been boiled at some point to remove any impurities, but I didn’t ask. I would have liked to try a more traditional southern snack of boiled peanuts, but mashing them into hummus seemed neither right nor appetizing. Our bartender was a tall, slim man wearing black pants and a white collared shirt with sleeves rolled up to the elbows, and sported a well manicured but not too tame mid-length beard complimented by a mostly short cropped head of hair. (I say mostly because there remained a slicked back tuft on top of his head, which must have been too hard to reach with a hand cranked, artisanal shaving tool.) I wondered why he spent so much time confiding in the mirror until I realized he was talking to a second bartender, a tall, slim man wearing the same clothes and hair as he was. Both men’s ensembles were brought together with suspenders in a subtly Southern way.

What to one man is a fashion accessory is to another a necessity. Over at Prohibition, the bartenders wore suspenders to literally hold their ensembles – jeans, plaid shirts, beer bellies – together. Men too old to be shooting tequila on a Saturday afternoon were yelling at their teams as college football games were broadcast over several TVs. Even if we hadn’t been a Yankee and a foreigner, it sill wouldn’t have been wise to ask to turn on the hockey game. While Proof played on the exclusivity of the speakeasy from America’s underground alcohol culture, Prohibition glorified its backwoods bootlegger.

Being a visitor in Charleston is like being at a Halloween party without a costume. Everyone is somebody - somebody Southern - except you. Our introduction to the more reserved side of Charleston society was at Hall’s Chophouse. Hall’s is the restaurant everyone told us is the best place to eat when someone else is paying. The owner personally greets everyone who walks through the door in what I assumed was an act to play up southern charm and hospitality, but was more likely a sincere effort to make diners feel welcome – treatment you rarely receive in New England restaurants of the same caliber. We were immediately introduced to a charismatic man who owned a well-known car dealership in town. Actually, to call him charismatic is a bit of an understatement and not quite accurate. He simply holds court. In the twenty minutes we spent talking to him he called an economics professor away from his table to ask what the hell an economics lab was if it didn’t have a supply of beakers and test tubes and rallied a preacher he called “the Reverend”, who happened to be walking by, into prayer for us and our trip, all while holding three separate conversations between our group. Eventually he excused himself, telling us that if he didn’t get going his wife would start the fight without him, and we were seated for dinner.

The only thing better than the company and entertainment at Hall's was the food. My dad’s friends from Newport who spend a lot of time in Charleston generously treated us to some of the best steak and Brussels sprouts I’ve ever had, as well as sharing some tips about routes, anchorages, and stopping points between South Carolina and the Bahamas. After dinner we met a man who had spent some time in Newport. He, too, offered his suggestions for eating in the city and we mentioned that we wanted to try the oysters at a place called Bowen’s Island outside of Charleston but didn’t have any way of getting there. He offered (insisted) to take us over the weekend so we exchanged numbers and it was settled.

The other thing about Charleston is everyone, including your cab driver, has an opinion on oysters. On the halfshell is typically how I prefer them, but on arriving in Charleston I was searching for the best place to get chargrilleds after my friend Ted turned me onto them last year. I read about oyster roasts, which I guess are the equivalent of our clambakes up north. And then learned about lightly steamed cluster oysters at a place out in the marshes of Bowen's Island and we made it our mission to get there.

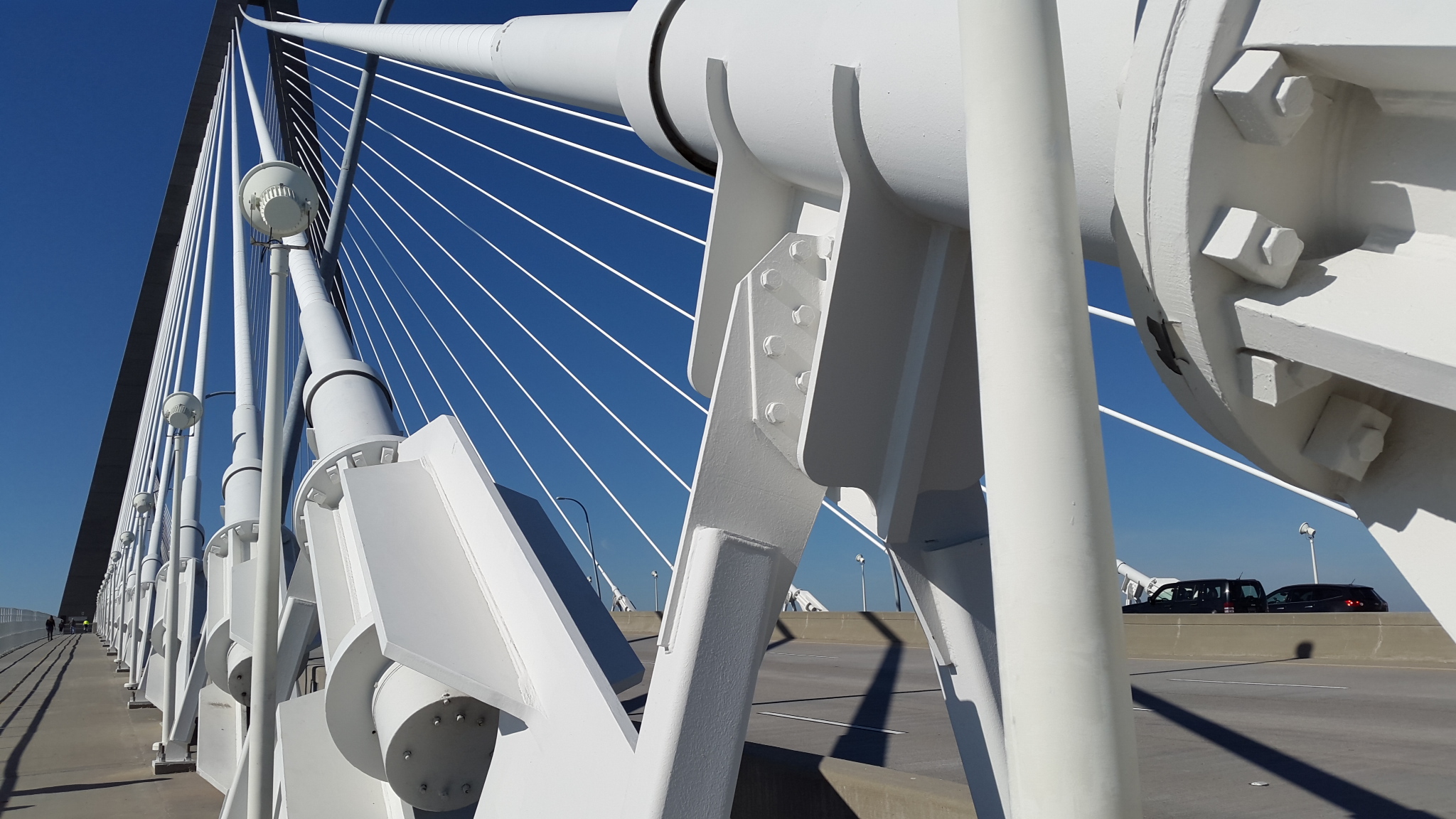

In the city, the charm is decidedly Southern. Just outside, though, what you experience is a bit more raw. Cross one of the bridges that take you off the peninsula where Charleston sits and visit any of the shrimp docks or oyster houses along the inlets and creeks the wind their way through the marshes and you’ll understand what lowcountry means. One specific example is the woman we ran into on while walking around one of the seafood docks over in Mount Pleasant on Thanksgiving day. She was fishing in what must have been a foot of water, cigarette in mouth, beer in hand, and massive chocolate lab called Cookie by her side. She told me she was gonna get one, she knew there were flounder down there, she seen a big one. I told her all she needed was patience, and she agreed, I think, with a swig of beer. Unfortunately patience wasn’t all she needed… I use “fishing” as a loose term here; there wasn’t a lot of action involved. There was a rod, some line, a red and white plastic bobber. Other than that there was the beer drinking and the waiting. Around the corner the smoker was going, country music blasting, half a dozen pickup trucks parked outside. We also found a piece of chicken skin and a human tooth further down the dock. One huge guy gave us barely understandable directions to the nearest corner store to pick up some beers – I assumed at the time he meant for ourselves, sort of an invitation to join what I guess was a party? I realize now he’d likely run out of Bud heavy. I wanted to stay, but I’d actually made some traditional Thanksgiving food (suddenly so boring) so we had to leave. Also, I really don’t think we were welcome.

A broader and (for most people) more inviting representation of the Lowcountry is Bowen’s Island. We’d planned to meet our new friend Scott there to eat oysters while watching the sun set over the marshes. I was expecting a sort of Martha Stewart does Charleston oyster jubilee with twinkling lights and cheesy music playing but it was anything but. The building was raised on stilts, constructed with 2x4s, plywood and cinderblock and paneled on the west with glass windows. There was a sweaty guy steaming oysters in a tiny corner of the cavern-like basement where you had to go to pick up your order. Upstairs it was loud, crowded, warm, and lively. We waited in the stillness outside, our breath visible as the sun sank into the smoke hovering in the marshes.

The platter of oysters we ordered didn’t arrive arranged neatly on ice with lemon and horseradish but as a hunk of shell piled on shell atop a plastic school lunch tray, along with a handful of shucking knives and kitchen towels. One tray wasn’t enough. Two trays wasn’t really enough either so we got some peel and eat shrimp, something else you see all over the Carolinas. It was briny and messy and there was no attempt to be anything other than what it was. There were well-dressed families, guys in overalls who looked like they’d just stumbled over from a hog farm, hipsters, tourists, frat boys. That’s what makes Bowen’s Island such a cool place and unlike anywhere else in Charleston, where it seems like Southern has to mean something specific. Here was everything I thought of as Southern all in one place.

If there’s one stereotype about the South that’s true it’s that the people are more friendly than most places. We arrived in Charleston knowing nobody and left having visited some of the best places on our trip so far, thanks largely to the kindness of strangers.